-

Schaden & Unfall

Schaden & Unfall ÜberblickRückversicherungslösungenTrending Topic

Schaden & Unfall

Wir bieten eine umfassende Palette von Rückversicherungslösungen verbunden mit der Expertise eines kompetenten Underwritingteams.

-

Leben & Kranken

Leben & Kranken ÜberblickUnsere AngeboteUnderwritingTraining & Events

Leben & Kranken

Wir bieten eine umfassende Palette von Rückversicherungsprodukten und das Fachwissen unseres qualifizierten Rückversicherungsteams.

-

Unsere Expertise

Unsere Expertise ÜberblickUnsere Expertise

Knowledge Center

Unser globales Expertenteam teilt hier sein Wissen zu aktuellen Themen der Versicherungsbranche.

-

Über uns

Über uns ÜberblickCorporate InformationESG bei der Gen Re

Über uns

Die Gen Re unterstützt Versicherungsunternehmen mit maßgeschneiderten Rückversicherungslösungen in den Bereichen Leben & Kranken und Schaden & Unfall.

- Careers Careers

PFAS and Microplastics - The Next “Toxic Torts” on the Horizon?

15. Dezember 2020

Tim Fletcher

Region: North America

English

Chinese

For a number of years, Gen Re has maintained “Pollution Coverage Rulings & Maps,” a publication to inform clients of developments regarding the absolute pollution exclusion, the owned property exclusion and other related topics, such as coverage trigger, loss in progress defense, and whether or not cleanup costs constitute damages compensable under a Commercial General Liability policy.

In updating that publication for 2020, it’s become clear that the pace of change has remained relatively slow and that case law has stayed relatively stable. Interpretation of the Absolute Pollution Exclusion (APE) continues to vary by state, with few new precedent-setting decisions taking place.

While case law concerning certain “20th century” toxins - such as lead paint, PCBs, and environmental solvents - has largely matured, two other contaminants are poised to cast long shadows on both society at large and the insurance industry in particular: PFAS and plastics. Both carry the potential to impose significant health risks on humanity and by extension the insurance industry for the financial consequences of bodily injury and environmental remediation.

PFAS - The “Forever” Chemicals

Developed originally during the 1940s and known formally as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), there are some 4,000 of them in all. PFAS were originally developed to repel water, resist stains, extinguish fires, and keep food from sticking to cookware through such products as Teflon, fire-fighting foam and plastic food packaging. Ubiquitous in the environment - they’re in the blood of 95% of us, experts say - PFAS are suspected to adversely affect the liver, thyroid and immune system, while also thought to contribute to low birth weights and cause cancer.

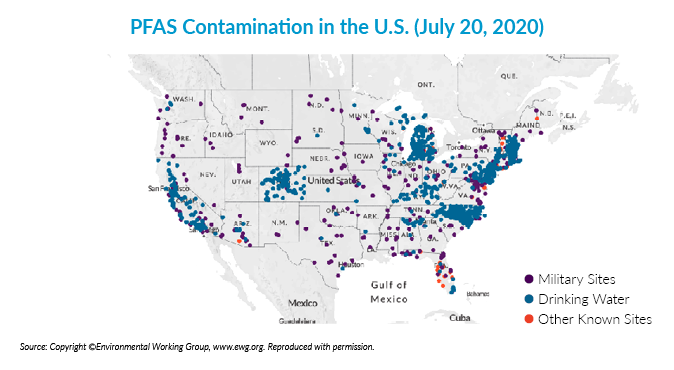

Called “forever chemicals” because of their imperviousness to disintegration, PFAS are present in many water supplies throughout the country. State and federal regulators are working to establish standards for what constitutes acceptable PFAS concentration levels, and science continues to quantify the links between PFAS and heath.

While these efforts continue, litigation has been marching forward for a number of years. Activity to date has consisted of class actions against PFAS chemical producers and, recently, against boot manufacturer Wolverine for water contamination arising from its use of Scotchgard. Multimillion-dollar settlements have resulted, but with only limited actions by the manufacturers against their insurers, seeking economic compensation and defense-cost reimbursement.

Against this unsettling backdrop come a number of coverage questions. For example, concerning the courts that have viewed the APE as applying only to “traditional” pollution, how will they treat PFAS? What about those policies that contain an APE but do not expressly exclude PFAS? Given the current scientific uncertainty, when does bodily injury from PFAS occur?

Plastic Contamination - The “Great Garbage Patch” and Beyond

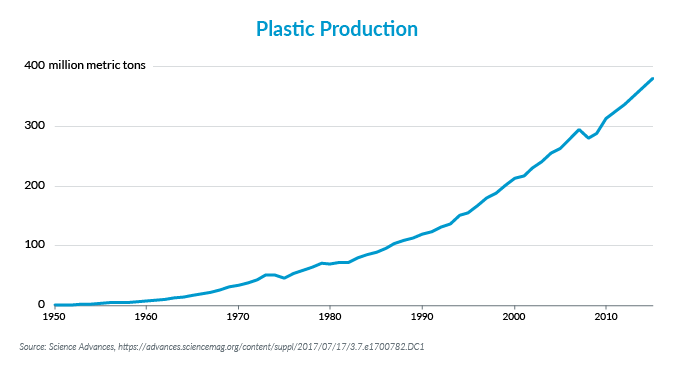

Plastic use has exploded since the 1960s - more than twentyfold since 1964 according to the World Economic Forum. These increases - combined with China’s 2018 decision to no longer accept many plastic waste products and heightened plastics consumption driven by the current pandemic - has resulted in plastics infiltrating all corners of the globe and posing a growing health danger.

Exacerbating the problem is that while plastics break up, they never completely decompose. To that end, microplastics (defined as less than five millimeters) have infiltrated water, marine wildlife and human beings. One Australian study estimated that the average person ingests roughly a credit card’s worth of plastics (5 grams) each week.

While studies confirming the pervasive presence of plastics have been increasing, the health effects have not been verified. Some evidence suggests that microplastics can cross the membrane that protects the brain from foreign bodies entering the bloodstream. Other studies suggest that microplastics could potentially leach harmful chemicals that could interfere with hormones and reduce fertility in men and women.

As with PFAS, scientific studies on the impact of microplastics continue. Growing connections between microplastic ingestion or exposure and adverse health effects will inevitably unleash litigation aimed at plastics producers and those companies that use plastics in their products. These companies may then turn to their insurers for defense and indemnification.

At first glance, it would seem that the APE would exclude such suits. However, the common APE does not define plastics as either a “pollutant” or “contaminant.” Moreover, a suit alleging a bodily injury from plastics may trigger an insurer’s duty to defend. Other liability coverages could be triggered as well, ranging from product liability for microplastic producers and product recall for polluted seafood products.

Conclusion

PFAS and microplastics are the most recent examples in a long line of exposures that were previously unseen. They ring an alarm bell while reminding us that word meaning and policy construction are vital to our industry. Precisely explaining what is covered - and what is not intended to be covered - will continue to challenge underwriters as previously unforeseen exposures manifest themselves.