-

Schaden & Unfall

Schaden & Unfall ÜberblickRückversicherungslösungenTrending Topic

Schaden & Unfall

Wir bieten eine umfassende Palette von Rückversicherungslösungen verbunden mit der Expertise eines kompetenten Underwritingteams.

-

Leben & Kranken

Leben & Kranken ÜberblickUnsere AngeboteUnderwritingTraining & Events

Leben & Kranken

Wir bieten eine umfassende Palette von Rückversicherungsprodukten und das Fachwissen unseres qualifizierten Rückversicherungsteams.

-

Unsere Expertise

Unsere Expertise ÜberblickUnsere Expertise

Knowledge Center

Unser globales Expertenteam teilt hier sein Wissen zu aktuellen Themen der Versicherungsbranche.

-

Über uns

Über uns ÜberblickCorporate InformationESG bei der Gen Re

Über uns

Die Gen Re unterstützt Versicherungsunternehmen mit maßgeschneiderten Rückversicherungslösungen in den Bereichen Leben & Kranken und Schaden & Unfall.

- Careers Careers

Hyperlipidaemia – When Does it Get Really Dangerous?

15. August 2024

Dr. Sandra Mitic,

Elena Dorando

English

Hyperlipidaemia is an extremely common condition that describes various genetic or acquired disorders with elevated lipid levels. It is a contributing factor of cardiovascular disease: it promotes lipid deposits in the blood vessels which favours atherosclerotic plaque formation.

The recording of lipid parameters in laboratory diagnostics is of great importance for cardiovascular risk assessment and therapy management. Total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) have been the most-used parameters for cardiovascular risk assessment for several years. In recent years, other lipid parameters have appeared in the medical evidence, which have been investigated for additional informative value for determining cardiovascular risk.

This article deals with the question of which type of lipids should be measured to assess cardiovascular risk and which have the best predictive value for the development of atherosclerosis resulting in cardiovascular events.

What are lipids?

Blood fats in the human body are known as lipids. Some lipids serve as a source of energy, others take on important functions as structural components of cells and nerve sheaths, as hormones, vitamins, etc. Lipids are either ingested with food or are formed in the liver or fatty tissue of the organism.

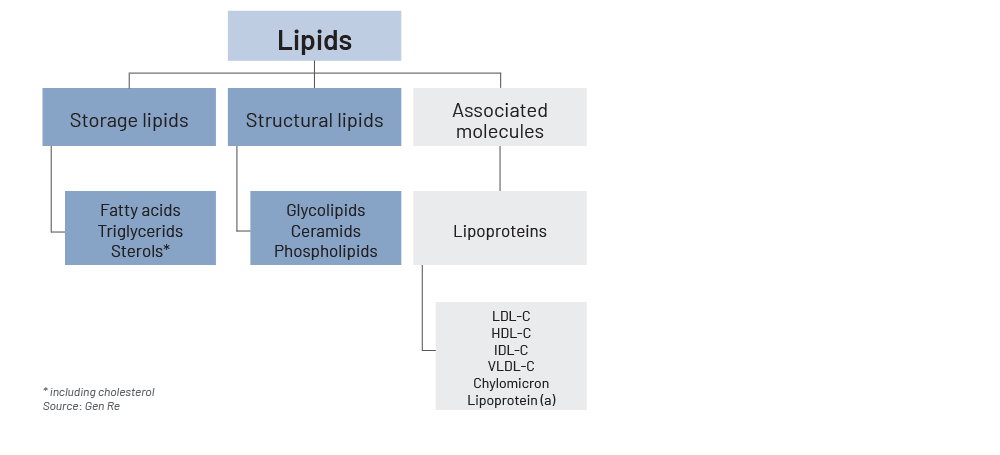

Lipids can be classified according to their function as storage lipids or structural lipids. Storage lipids store energy, while membrane lipids contribute to the structural integrity and fluidity of cell membranes. An additional group in the functional classification comprises lipoproteins, subclassified into different subtypes according to their density (see Figure 1).1 As fats are not soluble in water, lipoproteins are needed for their transport through the bloodstream to different body cells.

Figure 1 – Types of lipids

Lipid measurement

The concentration of plasma lipoproteins is usually not measured directly but estimated by measuring their cholesterol content. TC is the sum of individual cholesterol contents, bound to different types of lipoproteins. While very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), LDL and HDL contain larger proportions of cholesterol, intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL) and lipoprotein (a) contain smaller amounts.

The standard lipid serum lab profile measures TC, HDL and TG. LDL is estimated using the Friedewald formula (LDL= TC - HDL - [TG/5] in mg/dL). It should be noted that this formula is applicable only if TG values are ≤ 400 mg/dL (≤ 4.5 mmol/L).2

Basic lipid blood parameters

Enhancers of cardiovascular disease (CVD) can be found in Table 1.

Table 1 – Blood parameters and their effect on cardiovascular disease

|

Parameter |

Enhancer of CVD |

Comment |

|---|---|---|

|

Total cholesterol (TC) |

✓ |

TC = LDL + HDL + cholesterol in triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and in lipoprotein (a) |

|

Triglycerides (TG) |

✓ |

Main constituents of body fat in humans |

|

Lipoprotein (a) (Lp[a]) |

✓ |

Independent genetic factor |

|

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) |

✓ |

Cholesterol carrier; direct atherogenic vascular effect |

|

Very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) |

✓ |

TG and cholesterol carrier |

|

Intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL) |

✓ |

TG and cholesterol carrier |

|

Trans fatty acids |

✓ |

Unsaturated fatty acids that come from industrial (fried or baked goods) or natural sources (meat or dairy products) |

|

Phosphatidylcholine |

✓ |

Key building parts for biological membranes, and plasma lipoproteins. Elevated in cancers because of the increased demand for membrane constituents, and linked to liver conditions, e.g. non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

|

Lysophosphatidic acid |

✓ |

Versatile signalling molecule with diverse effects on central nervous system and new blood vessel development. Can act as a powerful mediator of pathological conditions |

|

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) |

— |

Cholesterol carrier; low HDL level indicates a higher CVD risk |

|

Non-high-density lipoprotein (Non-HDL) |

✓ |

TC minus HDL=Non-HDL; important in high levels of TG |

|

Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) |

✓ |

Contains all atherogenic lipoproteins; important in high LDL levels |

Source: Gen Re

Total cholesterol

Total cholesterol includes LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and cholesterol associated with triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. These include VLDL cholesterol, IDL cholesterol or remnant cholesterol. The measurement of TC is necessary to calculate the non-high-density lipoprotein (non‑HDL) cholesterol value (TC minus HDL=Non‑HDL).3

LDL cholesterol

Low-density lipoprotein consists of a molecule of apolipoprotein B (ApoB), other apolipoproteins, and a variable number of cholesterol molecules. There are different subtypes of LDL that differ in their atherogenic attitude, but a determination of LDL subtypes is not recommended, as the evidence regarding risk reduction through lipid lowering is based on the measurement of LDL cholesterol (and not its subtypes). Lowering the LDL cholesterol concentration is the primary treatment goal.4

HDL cholesterol

Similar to LDL cholesterol, different HDL subfractions can be distinguished, which differ in their apolipoprotein composition and also the amount of cholesterol transported. Low HDL cholesterol levels indicate inflammation or metabolic problems, especially diabetes and correlate with an increased risk of cardiovascular events.5

Triglycerides

Triglycerides are also transported on different lipoproteins, mostly on VLDL, chylomicrons and chylomicron remnants. The TG concentration correlates with the cardiovascular event rate, but the increased cardiovascular risk is not caused by triglycerides directly. Atherosclerotic pathogens are primarily the cholesterol contained in the TG‑rich lipoproteins such as VLDL, the particles themselves and the change of LDL and HDL metabolism, which is caused by the increased concentration of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins.

The risk associated with triglyceride-rich lipoproteins can be assessed by their amount of cholesterol (e.g. VLDL cholesterol or remnant cholesterol) or the ApoB level. The cholesterol associated with TG‑rich lipoprotein cholesterol is included in the non‑HDL cholesterol parameter.6

Non‑HDL cholesterol

Non‑HDL cholesterol is a calculated parameter: TC minus HDL. Non‑HDL summarises all cholesterol that cannot be assigned to HDL, i.e. is transported in ApoB-containing lipoproteins. This includes the cholesterol contained in the TG‑rich lipoproteins such as VLDL in addition to LDL and Lp(a). It is assumed that all ApoB-containing lipoproteins have a pro-atherogenic effect.

Non‑HDL cholesterol is therefore considered a global parameter for lipid-associated risk, similar to the ApoB concentration. The higher the serum TG values, the greater the superiority of non‑HDL cholesterol over LDL cholesterol in terms of risk stratification and therapy control. It is therefore particularly helpful to analyse non‑HDL cholesterol in patients with elevated TG levels.7

Lipoprotein (a)

Lipoprotein (a) levels are essentially genetically determined. The Lp(a) concentration is not normally distributed in the general population but is strongly shifted to the left (in the Gaussian distribution). This means that there are many people with very low Lp(a) levels and a few with excessively high levels. There are ethnic and gender-specific differences in Lp(a) concentration. Women have on average 5 to 10% higher Lp(a) values than men. Furthermore, renal dysfunction may increase Lp(a) values, while impaired liver function may lead to decreased Lp(a) plasma concentration. But most importantly, diet and physical activity have no influence and oral lipid-lowering drugs hardly affect Lp(a) levels.8

Apolipoprotein B

The plasma concentration of ApoB shows a close correlation with cardiovascular risk, similar to the non‑HDL cholesterol concentration. Determination of the ApoB concentration can be helpful to further clarify an “apparent” increase in LDL concentration in cholestatic liver diseases. If ApoB is also elevated in this situation, this indicates an actual increase in atherogenic lipoproteins. If the ApoB concentration is discordant with the LDL cholesterol concentration, this indicates the presence of abnormal lipoproteins, which is typical of cholestasis.9

Which lipids are of concern?

Different perspectives, different preferred lipid parameters

To decide which lipid parameter is “the best”, one must define the outcome of interest as this depends on what is being attempted by evaluating a lipid profile.

The primary focus in clinical practice is on defining the “right” moment for treatment, on determination of the most suitable type of treatment, and on monitoring hyperlipidaemia with the aim of reducing cardiovascular risks. In an insurance underwriting context, predicting all-cause and cardiovascular-specific mortality and morbidity risk is primarily relevant. Different lipid parameters have been shown to be better suitable for the two different objectives of (a) managing and monitoring treatment success, and (b) predicting absolute or relative cardiovascular risk.10,11

Treatment selection and monitoring perspective

Treatment success is defined as the effectiveness of a particular intervention in achieving a specific outcome. For example, a cholesterol-lowering medication in the clinical context is considered successful if it reduces LDL cholesterol levels to a certain target range.

Like other lipid parameters, LDL is associated with increased risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).12 People with primary elevations of LDL cholesterol are at a higher risk of ASCVD as a result of a long-term exposure to markedly elevated LDL levels, even in the absence of pre-existing ASCVD.13

LDL and/or non‑HDL are usually chosen as the preferred marker to monitor treatment success, as they are more responsive to treatment than other lipid parameters. For example, LDL and non‑HDL ranked highest for treatment response to initial statin treatment in a population with previous acute coronary syndrome.14

Lowering of LDL cholesterol is widely accepted as a key objective in the prevention of cardiovascular disease.15 As an example, the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study, a large randomised controlled trail with a 20‑year follow‑up of almost 7,000 men with high LDL levels identified a continued benefit from five years of lowering LDL cholesterol with a statin. It showed decreased mortality from cardiovascular causes and an ongoing reduction in cardiovascular hospital admissions.16

This positive effect has been confirmed by other studies. The proportional reduction in ASCVD achieved by lowering elevated LDL cholesterol depends on the absolute reduction in LDL cholesterol, with each 1 mmol/L reduction corresponding to a reduction of about 20% in ASCVD.17

Controversy remains about which people to treat and which goals to achieve, and about the extent of benefits and potential harms in the context of primary prevention.18

US population studies suggest that optimal total cholesterol levels are about 150 mg/dL (3.8 mmol/L), which corresponds to an LDL cholesterol level of about 100 mg/dL (2.6 mmol/L). Adult populations with cholesterol concentrations in this range manifest low rates of ASCVD.19 The European guidelines consider LDL cholesterol target levels of <116 mg/dl (3.0 mmol/L) as the target value.20

However, there is no “one” specific LDL cut‑off value that should not be exceeded. The amount of blood cholesterol allowed to circulate in the blood depends on age, sex and numerous other risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. These risk factors include obesity, lack of exercise, smoking, family history of lipometabolic disorders, family history of stroke or heart attack and high-fat diet.

Previous illnesses are also taken into account. Defined pre-existing conditions for which elevated LDL levels should be lowered include type II diabetes, high blood pressure, pre-existing vascular diseases (e.g. stroke, heart attack, etc.), elevated TG, liver steatosis or history of acute pancreatitis.21

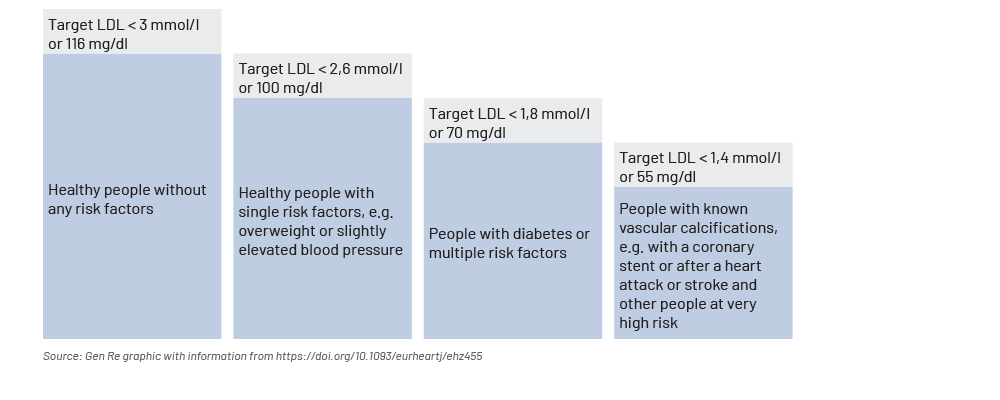

All major current guidelines on the prevention of ASCVD recommend an assessment of a total coronary vascular disease risk. Accordingly, different health risk groups result in different target values for LDL. As a general rule of thumb: the higher the number of a single risk for developing cardiovascular disease or with already existing cardiovascular diseases, the more intense the action should be to lower the target value for LDL levels (see Figure 2).

- For healthy people without any risk factors, an LDL cholesterol value <116 mg/dL (<3.0 mmol/l) is considered the target value.

- For healthy people with single risk factors, e.g. overweight or with slightly elevated blood pressure, the LDL cholesterol value should be <100 mg/dL (<2.6 mmol/l).

- Patients with diabetes or multiple risk factors should aim for an LDL cholesterol of <70 mg/dL (<1.8 mmol/l).

- For people with known vascular calcifications, e.g. with a stent in the coronary arteries or patients after a heart attack or stroke and other people at very high risk, the LDL cholesterol target value is <55 mg/dL (<1.4 mmol/l).22

Figure 2 – Guideline values in the management of cholesterol levels

Risk prediction perspective

“Risk prediction” for mortality and morbidity refers to the relative likelihood of a person experiencing a certain outcome, such as ASCVD or death.

Cardiovascular risk prediction of applicants is an essential part of underwriting insurance. In clinical practice, cardiovascular risk prediction also plays a role for the initial assessment of the individual patient,23 but it is generally less present than the objective of optimal treatment management.

For the general risk prediction perspective, lipid parameters with the best predictive value for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality and morbidity risk are preferred. Although various lipid parameters are correlated with each other and are associated with cardiovascular risk (positively or negatively) to some extent, some parameters predict future risk better than others.24

For this perspective, parameters used for treatment monitoring, such as LDL, play only a subordinate role. Here, the TC:HDL ratio has shown better predictive value and risk discrimination than LDL cholesterol alone.25,26 This was indicated in studies with a population with previous acute coronary syndrome,27 as well as in a population without previous cardiovascular events.28 Other ratios, such as the LDL:HDL ratio or ApoB:ApoA‑I ratio showed comparable results but were not superior to TC:HDL ratio in this study.29

Furthermore, several scientific data analyses and ASCVD risk prediction models used TC:HDL ratio instead of LDL as it shows better risk discrimination abilities.30,31 This includes for example the SCORE calculator recommended by the European treatment guidelines for management of dyslipidaemia and the risk prediction model QRISK3, which is recommended by UK treatment guidelines.32,33,34,35,36

Value of adding further lipid parameters to risk prediction models

Several studies have investigated whether including additional lipid parameters to the risk prediction model would improve its predictive value compared to risk prediction based on TC and HDL, i.e. the TC:HDL ratio.37,38,39

Triglycerides are part of the standard lipid profile, and were included in prediction models in the past. While it is recommended to assess plasma TG in clinical practice to identify those individuals with underestimated modifiable ASCVD risk,49 TG has shown no additional value in risk prediction models when investigated on population level. Reviews and meta-analyses of primary studies have shown that after adjusting for TC, the impact of TG becomes insignificant for predicting ASCVD risk and all-cause mortality.41,42

Additional lipid parameters, including ApoB and Lp(a), were investigated by the Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration for their impact on ASCVD risk prediction. They found that replacing TC and HDL with those parameters did not improve risk discrimination or reclassification and instead worsened the model.43 When the above-mentioned parameters were added to TC and HDL in the model, ASCVD risk prediction improved minimally.44 Further research indicates that ApoB can improve risk prediction in a specific subpopulation, in which non‑HDL and ApoB levels are discordant. In this subpopulation non‑HDL appears to be normal, but ApoB levels are elevated.45

In conclusion, while several lipid parameters have been thoroughly researched for their potential to improve risk prediction models for cardiovascular disease, the evidence suggests that the TC:HDL ratio remains the best predictor for the average population. While some parameters, such as ApoB, may provide slight improvements for specific sub-populations, the availability and cost-effectiveness of using the TC:HDL ratio makes it the preferred primary tool for lipid-based risk assessment in clinical practice and in underwriting.

Conclusion

Lipid parameters play an important role in assessing and modifying ASCVD risk. In summary, the choice of the best lipid parameter to assess hyperlipidaemia and predict cardiovascular risk, all-cause mortality and morbidity depends on the outcome of interest. For treatment selection and monitoring in clinical practice, LDL and non‑HDL are usually used, as they are more responsive to treatment than other lipid parameters.

For underwriting and predicting future risk however, the lipid parameters with the best predictive value are preferred. Here, the TC:HDL ratio is considered the best suitable measure due to its predictive value for the average population and its availability. Further lipid parameters, such as ApoB or Lp(a), can be helpful to identify applicants with discordant lipid values and be used as a secondary parameter in the model, if they are available.

It is important to note that the best predictive value is achieved with models that use lipid parameters in combination with additional ASCVD predictor variables, such as blood pressure, body mass index, diabetes, and smoking status.

- Bhargava, S., de la Puente-Secades, S., Schurgers, L., et al. (2022). Lipids and lipoproteins in cardiovascular diseases: a classification. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism, 33(6), 409–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2022.02.001

- Mach, F., Baigent, C., Catapano, A. L., et al. ESC Scientific Document Group (2020). 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. European Heart Journal, 41(1), 111–188. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ingelsson, E., Schaefer, E. J., Contois, J. H., et al. (2007). Clinical utility of different lipid measures for prediction of coronary heart disease in men and women. JAMA, 298(7), 776–785. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.7.776

- Glasziou, P. P., Irwig, L., Kirby, A. C., et al. (2014). Which lipid measurement should we monitor? An analysis of the LIPID study. BMJ Open, 4(2), e003512. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003512

- Grundy, S. M., Stone, N. J., Bailey, A. L., et al. (2019). 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 73(24), e285–e350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003

- Vallejo‑Vaz, A. J., Robertson, M., Catapano, A. L., et al. (2017). Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Lowering for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Among Men With Primary Elevations of Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels of 190 mg/dL or Above: Analyses From the WOSCOPS (West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study) 5‑Year Randomized Trial and 20‑Year Observational Follow‑Up. Circulation, 136(20), 1878–1891. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027966

- Glasziou, P. P., Irwig, L., Kirby, A. C., et al. (2014). Which lipid measurement should we monitor? An analysis of the LIPID study. BMJ open, 4(2), e003512. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003512

- Ford, I., Murray, H., McCowan, C., et al. (2016). Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of Lowering Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol With Statin Therapy: 20‑Year Follow‑Up of West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. Circulation, 133(11), 1073–1080. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019014

- Ibid

- Mach, F., Baigent, C., Catapano, A. L., et al. ESC Scientific Document Group (2020). 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. European Heart Journal, 41(1), 111–188. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455

- Ford, I., Murray, H., McCowan, C., et al. (2016). Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of Lowering Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol With Statin Therapy: 20‑Year Follow‑Up of West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. Circulation, 133(11), 1073–1080. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019014

- Grundy, S. M., Stone, N. J., Bailey, A. L., et al. (2019). 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 73(24), e285–e350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003

- Mach, F., Baigent, C., Catapano, A. L., et al. ESC Scientific Document Group (2020). 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. European Heart Journal, 41(1), 111–188. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, Di Angelantonio, E., Gao, P., Pennells, L., et al. (2012). Lipid-related markers and cardiovascular disease prediction. JAMA, 307(23), 2499–2506. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.6571

- Ingelsson, E., Schaefer, E. J., Contois, J. H., et al.(2007). Clinical utility of different lipid measures for prediction of coronary heart disease in men and women. JAMA, 298(7), 776–785. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.7.776

- Glasziou, P. P., Irwig, L., Kirby, A. C., et al. (2014). Which lipid measurement should we monitor? An analysis of the LIPID study. BMJ open, 4(2), e003512. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003512

- Ibid

- Ingelsson, E., Schaefer, E. J., Contois, J. H., et al.(2007). Clinical utility of different lipid measures for prediction of coronary heart disease in men and women. JAMA, 298(7), 776–785. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.7.776

- Ibid

- Hippisley‑Cox, J., Coupland, C., & Brindle, P. (2017). Development and validation of QRISK3 risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 357, j2099. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j2099

- Nguyen, V. K., Colacino, J., Chung, M. K., et al. (2021). Characterising the relationships between physiological indicators and all-cause mortality (NHANES): a population-based cohort study. The Lancet. Healthy longevity, 2(10), e651–e662. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2666-7568(21)00212-9

- Hippisley‑Cox, J., Coupland, C., & Brindle, P. (2017). Development and validation of QRISK3 risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 357, j2099. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j2099

- Mach, F., Baigent, C., Catapano, A. L., et al. ESC Scientific Document Group (2020). 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. European Heart Journal, 41(1), 111–188. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455

- European Society of Cardiology (n.d.) Heart Score. EAPC. Retrieved January 10, 2023 from https://heartscore.escardio.org/Calculate/quickcalculator.aspx?model=low&_ga=2.226817310.2094252892.1675065146-1083126145.1675065146

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2023). Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification. NICE. Retrieved June 5, 2023 from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181/chapter/Recommendations#identifying-and-assessing-cardiovascular-disease-risk-for-people-without-established-cardiovascular

- Khan, S. S., Coresh, J., Pencina, M. J., et al. Novel Prediction Equations for Absolute Risk Assessment of Total Cardiovascular Disease Incorporating Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 148(24), 1982–2004. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001191

- Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, Di Angelantonio, E., Gao, P., Pennells, L., et al. (2012). Lipid-related markers and cardiovascular disease prediction. JAMA, 307(23), 2499–2506. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.6571

- Liu, J., Zeng, F. F., Liu, Z. M., et al. (2013). Effects of blood triglycerides on cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 61 prospective studies. Lipids Health Dis, 12, 159. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-12-159

- Sniderman, A. D., Islam, S., Yusuf, S., et al. (2012). Discordance analysis of apolipoprotein B and non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol as markers of cardiovascular risk in the INTERHEART study. Atherosclerosis, 225(2), 444–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.08.039

- Mach, F., Baigent, C., Catapano, A. L., et al. ESC Scientific Document Group (2020). 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. European Heart Journal, 41(1), 111–188. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455

- Liu, J., Zeng, F. F., Liu, Z. M., et al. (2013). Effects of blood triglycerides on cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 61 prospective studies. Lipids Health Dis, 12, 159. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-12-159

- Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, Di Angelantonio, E., Gao, P., Pennells, L., et al. (2012). Lipid-related markers and cardiovascular disease prediction. JAMA, 307(23), 2499–2506. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.6571

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Sniderman, A. D., Islam, S., Yusuf, S., et al. (2012). Discordance analysis of apolipoprotein B and non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol as markers of cardiovascular risk in the INTERHEART study. Atherosclerosis, 225(2), 444–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.08.039

All endnotes last accessed on 23 July 2024.